Lomas Rishi Cave is a 1,500-year-old marvel carved from a massive boulder near Gaya in Bihar, India. It’s part of the Barabar Hill Caves, the oldest surviving rock-cut caves in the country, dating back to the Mauryan Empire (322–185 BCE). Located around 25 km (15 mi) north of Gaya in Bihar, India, these ancient caves, some adorned with Ashokan inscriptions, stand as testaments to a bygone era.

The Barabar caves are found in a group of hills made of granite, near the Phalgu river, north of the town of Gâya. There are seven caves in total, and although they have different shapes, they are all similar and seem to have been made around the same time. They are not very big. The largest one is called the Nagarjuni cave, and it is a simple hall with circular ends, measuring 46 feet by 19 feet 5 inches. Two other caves, Sudama and Lomas Rishi, are almost as big, but they are divided into two parts, so they don’t have as much free space.

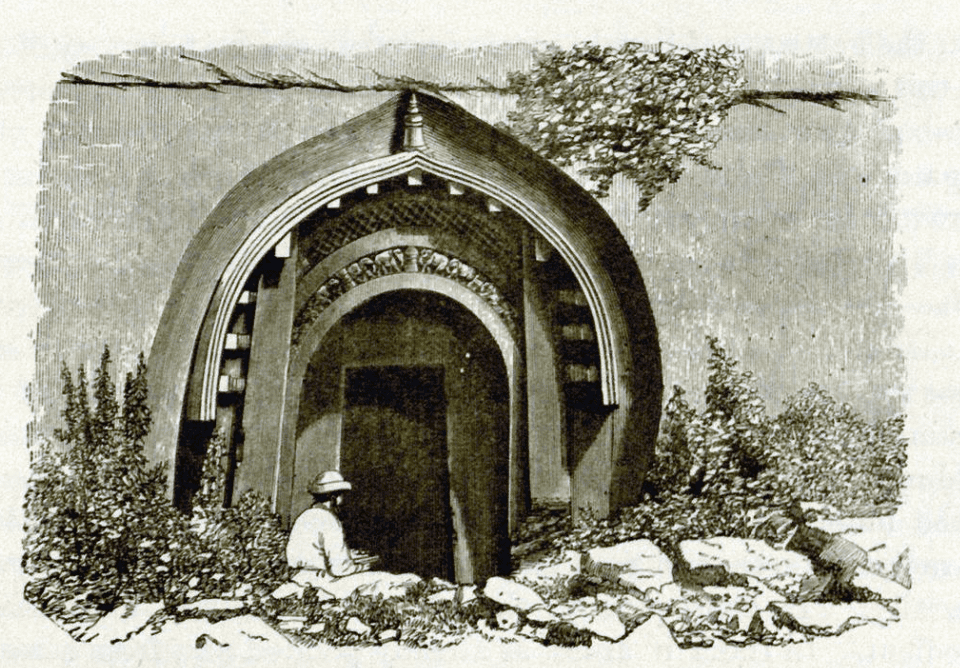

Among the Barabar Caves, Lomas Rishi Cave holds a special allure, renowned for its exquisitely carved door and intricate architecture. Situated on the southern side of the Barabar granite hill, it stands adjacent to the Sudama cave, forming a captivating ensemble of ancient craftsmanship.

Stepping inside Lomas Rishi Cave reveals its unique layout—a rectangular room measuring 9.86×5.18m leads to a circular, semi-hemispherical room 5m in diameter, connected by a narrow rectangular passage. The cave’s arched facade, reminiscent of contemporary wooden architecture, captures the imagination with its ornate details.

Adorning the periphery of the door, a procession of elephants marches along the curve of the architrave, flanked by stupa emblems. This distinctive feature, known as the “Chaitya arch” or chandrashala, has been a hallmark of Indian architecture and sculpture for centuries, reflecting a fusion of stone and organic forms.

Six out of the seven caves have inscriptions on them, written in the oldest form of the Pali alphabet, which is the same as the writing on Aśoka’s lâts. The inscription on the Sudama cave tells us it was made in the 12th year of a king, around 252 B.C. That makes it the oldest cave in the group. The newest one, the Gopi or Milkmaid cave in Nagarjuni hill, was made during the reign of Daśaratha, Aśoka’s grandson, around 214 B.C. So, all the caves were made within about 40 years of each other, starting around 80 years after Alexander the Great visited India.

As visitors explore the depths of Lomas Rishi Cave, they are transported back in time, marveling at the skill and artistry of ancient craftsmen who carved this sanctuary from solid rock. Whether used for religious rituals or communal gatherings, the cave stands as a testament to India’s rich cultural heritage and enduring architectural legacy, inviting admiration and wonder for generations to come.

Source: Fergusson, James R., and James Burgess. “Chapter I.—Barabar Group.” In The Cave Temples of India, 37-42. London: W. H. ALLEN & Co., et al, 1880.